Imagine a merchant in the city of Ur, around 2000 BCE. He wants to send a message to a trading partner in Dilmun, across the Persian Gulf, about a shipment of copper. He cannot write — fewer than one person in a hundred can. So he walks to the temple district and pays a scribe, who listens to his message and presses it into a damp clay tablet in careful cuneiform. The tablet is sealed, dried, and sent with a caravan. When it arrives in Dilmun, the trading partner cannot read it. He pays another scribe to read the message aloud. Two middlemen, two fees, for a single sentence. And the merchant has no way of knowing whether either scribe got his words exactly right.

Replace “scribe” with “developer” and “clay tablet” with “app,” and you have described the technology industry of 2024.

The Sumerian scribe charged two shekels of silver per tablet. A freelance React developer charges rather more — but the dynamic is identical. You have an idea in your head. You cannot manifest it in the medium. You pay someone who can. They may or may not understand what you actually wanted. And if you want changes, you pay again.

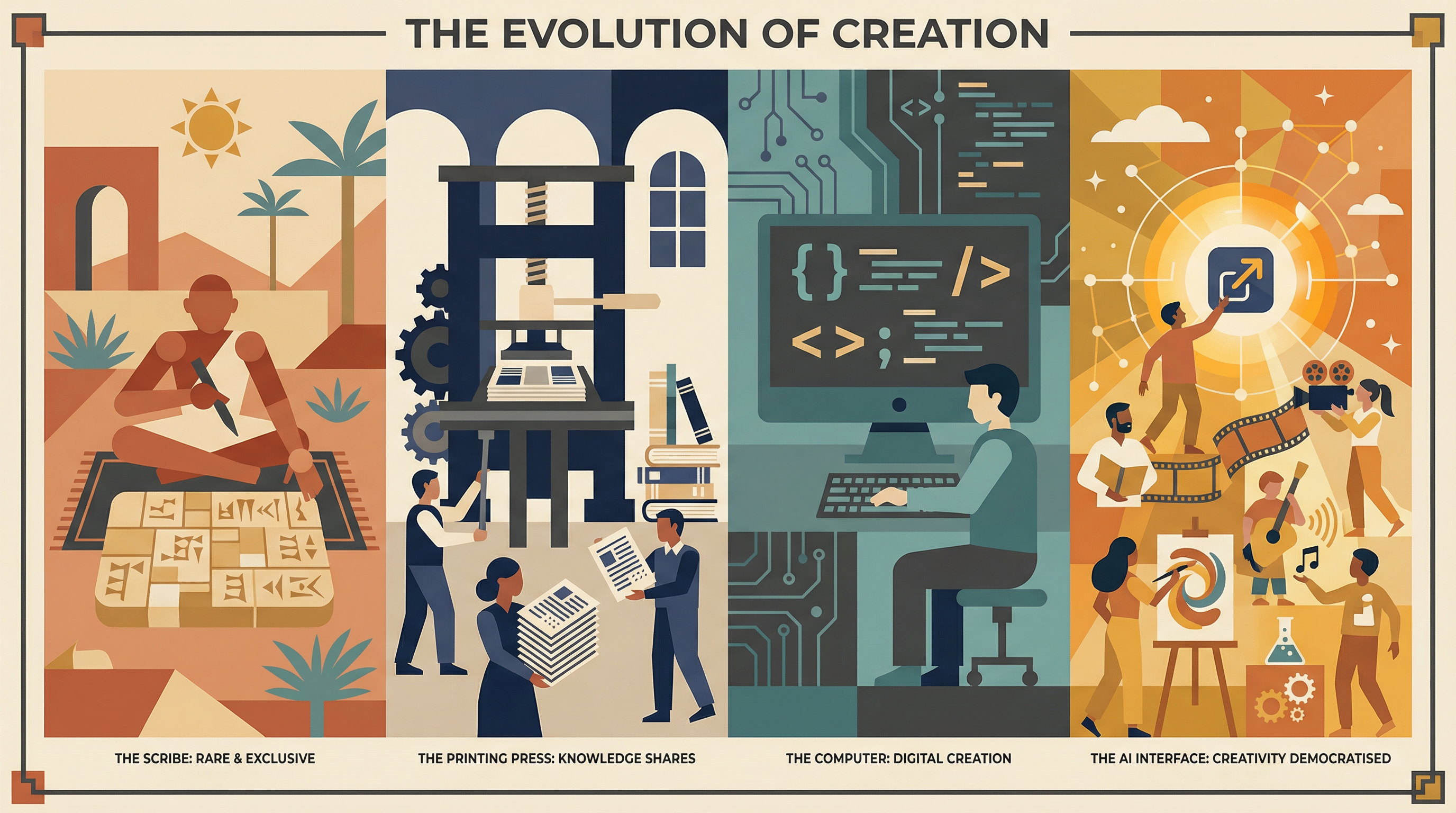

This article argues that artificial intelligence is doing to the digital scribal class — developers, designers, filmmakers, marketing strategists — what the printing press did to the monastic copyists and what mass literacy did to the scribes of the ancient world. The middlemen are being eliminated, and an extraordinary flourishing of human creativity is beginning. But history also reveals a darker pattern that follows every such democratisation: dependency and, eventually, atrophy. The question is not whether the flourishing will happen — it already is — but how long it lasts before we stop doing things ourselves entirely.

The Scribes’ Monopoly: Five Thousand Years of Cognitive Middlemen

Writing was invented in Sumer around 3200 BCE, not for poetry or philosophy but for accounting — recording grain stores, tax payments, and livestock inventories. For its first two and a half millennia, writing remained the exclusive property of a tiny caste. Literacy rates in ancient Mesopotamia, Egypt, and the early civilisations of the Indus Valley and China are estimated at well below one per cent of the population. The scribes were not merely useful; they were indispensable. Every contract, every law, every religious text, every diplomatic letter, every tax record — all passed through their hands.

Global Literacy Rates Over Five Thousand Years

For most of human history, fewer than five per cent of people could read or write. The alphabet, printing press, and compulsory education each triggered step-changes — AI may be triggering the next.

Source: Our World in Data (2023); Harris, Ancient Literacy (1989); Havelock (1982); UNESCO

This gave scribes extraordinary power. In Egypt, the scribal profession became a gateway to the priesthood and the bureaucracy. The Satire of the Trades, a Middle Kingdom text from around 1900 BCE, describes every other occupation as miserable — the soldier is beaten, the farmer is exhausted, the washerman stinks — while the scribe sits in comfort and commands respect. “Be a scribe,” the text urges, “for it frees you from toil.” The scribes did not merely record the will of the powerful; they shaped it. If you could not read a contract, you could not verify its terms. If you could not write a petition, you could not seek justice. The scribes were the interface between the individual and every institution that mattered.

This dynamic — the individual separated from their own intentions by a specialist intermediary — persisted for millennia. It is the fundamental condition of pre-literate society, and it lasted far longer than most people realise.

The Three Revolutions That Killed the Scribes

Three innovations, spread across three millennia, progressively demolished the scribes’ monopoly.

The first was the alphabet. Around 1050 BCE, the Phoenicians developed a writing system of roughly twenty-two consonantal signs — a radical simplification from the hundreds of cuneiform characters or Egyptian hieroglyphs that had previously required years of memorisation. The Phoenician alphabet was not invented for literature; it was invented for trade. Merchants needed a writing system simple enough that they could learn it themselves, without years of scribal training. The Greeks adopted and expanded this system around 800 BCE, adding vowels and creating the first fully phonetic alphabet.

The consequences were revolutionary. Within two centuries, Greek literacy rates rose to an estimated ten to fifteen per cent of adult males — low by modern standards, but a tenfold increase over anything the ancient Near East had achieved. This wider literacy enabled philosophy (Socrates could assume literate interlocutors), drama (audiences could follow complex written plots), history (Herodotus and Thucydides wrote for readers, not listeners), and — most consequentially — democracy. The Athenian Assembly, with its written laws, published decrees, and literate citizen-jurors, would have been impossible without the alphabet’s democratisation of writing. The scribes did not disappear overnight, but their monopoly was broken. Ordinary citizens could, for the first time, read the laws that governed them and write the arguments that shaped them.

The second revolution was the printing press. When Johannes Gutenberg printed his Bible around 1440, a handwritten book cost roughly the same as a small house. Within fifty years, the cost of a printed book had fallen by eighty per cent. Within a century, there were an estimated twenty million volumes in circulation in Europe. The monastic copyists — the medieval equivalents of the Sumerian scribes — were destroyed as a profession. But what replaced them was immeasurably greater: the Reformation, the Scientific Revolution, the Enlightenment, the novel, the newspaper, the political pamphlet, and the written constitution. Martin Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses mattered not because they were written, but because the printing press ensured that everyone could read them. European literacy rates climbed from roughly five to ten per cent in 1400 to over fifty per cent by 1800 and above ninety-five per cent by 1950.

The pattern was unmistakable: the middlemen lost their livelihoods, but humanity gained its voice.

The third revolution was compulsory education. Prussia introduced mandatory schooling in 1763; Britain followed with the Elementary Education Act of 1870; France with the Ferry Laws of 1881-82. By the early twentieth century, virtually every developed nation had committed to universal literacy. The scribe — the cognitive middleman who had existed in every civilisation for five thousand years — was finally, comprehensively, extinct.

And the world that emerged was unrecognisable. The explosion of newspapers created informed publics and held governments to account. The novel gave ordinary people access to the inner lives of others. Scientific publishing accelerated discovery from a trickle to a torrent. The written constitution made the social contract legible to every citizen. Mass literacy did not merely distribute an existing capability more widely; it created entirely new forms of human expression, governance, and knowledge that had been literally unimaginable in a pre-literate world.

The New Scribes: Coders, Designers, and the Digital Priesthood

Yet even as traditional literacy became universal, a new scribal class was forming.

The digital revolution created an entirely new medium — software — that was as opaque to the average person as cuneiform had been to the Sumerian merchant. If you wanted a website in 1995, you hired a developer. If you wanted a mobile app in 2010, you hired a development team. If you wanted a brand identity, you hired a designer. If you wanted a video advertisement, you hired a production company. If you wanted a marketing strategy, you hired an agency. The tools existed, but they required years of specialist training to use — just as cuneiform had required years of scribal education.

The numbers are striking. As of 2024, roughly 28 million people worldwide could write production-quality software — approximately 0.35 per cent of the global population. This is remarkably close to the literacy rates of ancient Mesopotamia. The remaining 99.65 per cent of humanity could no more build an application than a Bronze Age farmer could compose a legal contract.

The Scribal Economy Under Threat

Over $3 trillion in global "scribal" services — specialist intermediaries between people and digital creation — face AI-driven disintermediation.

Source: Statista (2025); McKinsey Global Institute (2023); Goldman Sachs (2023)

The economic structure that emerged around this digital illiteracy was enormous. The global IT services market reached $1.24 trillion in 2024. Creative services — design, video production, advertising, marketing — added another $600 billion. Combined, this “scribal economy” exceeded the GDP of all but a handful of nations. And the fundamental dynamic was precisely the same as it had been in Ur five thousand years ago: you had an idea in your head, you could not manifest it in the medium, you paid someone who could, and you hoped they understood what you meant.

Anyone who has commissioned software development will recognise the ancient merchant’s frustration. You explain your vision. The specialist interprets it through their own framework. What comes back is functional but not quite what you imagined. You request revisions. The cost escalates. The timeline extends. The specialist speaks a language you do not understand — React, APIs, databases, deployment pipelines — just as the scribe spoke a language the merchant could not verify. The “lost in translation” problem that haunted every interaction between the literate and the illiterate was alive and well in the twenty-first century.

The Printing Press Moment: 2024–2026

The Cost of Creating: Specialists vs AI Tools

AI has reduced the cost of digital creation by 80-95 per cent in under two years — a compression comparable to the printing press's impact on book production.

Source: Upwork (2024); Fiverr market data; industry estimates; author analysis

Then, in what will likely be seen as the most consequential eighteen months since Gutenberg, the cost and skill barrier collapsed.

The emergence of large language models capable of writing code — first tentatively with GitHub Copilot in 2021, then with increasing competence through 2023 and 2024, and finally with genuine autonomy in late 2025 — has reduced the barrier to software creation by roughly the same magnitude as the printing press reduced the barrier to book production. GitHub’s own research found that developers using Copilot completed tasks 55 per cent faster. But the more important finding, which emerged over the following two years, was that non-developers could now produce functional software at all.

By February 2026, the landscape has shifted from incremental improvement to qualitative transformation. Agentic AI systems — models that do not merely suggest code but orchestrate entire workflows, execute multi-step tasks, and deploy functioning applications — have moved from research curiosities to production tools. A teacher can describe a classroom management tool in plain English and have a working application within hours. A small business owner can produce broadcast-quality video advertisements without an agency. A novelist can generate illustrations for their book without an illustrator. An entrepreneur can build, test, and launch a SaaS product without an engineering team.

The parallel with Gutenberg is almost exact. The printing press did not make everyone a great writer; it made everyone capable of producing and distributing text. AI is not making everyone a great programmer; it is making everyone capable of producing and deploying software. The scribal monopoly — whether held by cuneiform specialists in 2000 BCE or React developers in 2024 — depended on the medium being inaccessible. When the medium becomes accessible, the monopoly collapses.

Who Can Code? The New Literacy Curve

Traditional developers number roughly 30 million. AI-assisted creators — people producing functional software with AI tools — are growing exponentially and may outnumber developers 10:1 by 2030.

Source: Evans Data Corporation (2024); GitHub; Stack Overflow Developer Survey; Gartner low-code forecasts

The investment community has noticed. Global AI spending is forecast to reach $2.52 trillion in 2026, a 44 per cent increase year-on-year. Much of this investment is a bet on precisely the disintermediation described here: that individuals and small teams, equipped with AI tools, will be able to do what previously required large specialist organisations.

Samsung’s Galaxy Unpacked event on 25 February 2026 promises “effortless AI” baked into consumer devices. Apple’s Siri overhaul, long rumoured, is reportedly centred on agentic capabilities — not answering questions but doing tasks. The India AI Impact Summit, which opened on 16 February 2026, has framed its agenda around “AI for welfare for all” — the democratisation thesis applied at the scale of a billion people.

The scribes are watching the printing press being assembled, and they can see exactly where this is going.

The Flourishing

History tells us what happens next: a flourishing.

When the printing press made text production cheap, it did not simply mean more copies of existing books. It meant entirely new forms of expression. The novel — a form that depends on mass readership — was essentially invented by the printing press. So was the newspaper, the scientific journal, the political pamphlet, and the written constitution. These forms could not have existed in a manuscript culture, not because no one thought of them, but because the economics of hand-copying made them impossible.

The AI-enabled flourishing is already visible, and it follows the same pattern of producing forms that could not previously exist:

Micro-SaaS. Individual creators are building niche software products for markets so small that no traditional company would serve them — a scheduling tool for independent dog groomers, an inventory system for small-batch hot-sauce producers, a practice-management app for speech therapists. These products are not simplified versions of enterprise software; they are perfectly tailored to needs that the software industry’s economics could never address.

The creator explosion. People who could not previously produce professional-quality media — short films, animations, music, games, illustrated books — are doing so. This is not the same as the earlier “democratisation” of tools like iMovie or GarageBand, which lowered the barrier modestly but still required significant skill. AI has lowered it almost to zero, making the gap between amateur and professional output narrower than it has ever been.

Small business empowerment. Marketing, branding, customer service, data analysis — capabilities that were previously accessible only to organisations large enough to employ specialists or hire agencies — are now within reach of a sole trader with a laptop. The corner shop can produce advertising that looks like it came from a London agency. The independent consultant can build a client portal that looks like it was built by a development team.

The parallel with the Reformation is instructive. Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses were not the first critique of the Catholic Church’s sale of indulgences — similar complaints had been made for centuries. But previous critiques remained local, because the manuscript economy could not distribute them. The printing press made Luther’s argument available to everyone who could read, and within a decade the religious and political map of Europe had been redrawn. AI is enabling people to act on ideas they previously could only have — just as the printing press enabled people to read arguments they previously could only hear about from someone who happened to have access to the manuscript.

This is the golden moment. History says it is real, and it is magnificent. Enjoy it while it lasts.

The Dependency Question: What Comes After the Flourishing

The Dependency Curve: Skill Atrophy After Tool Adoption

Every democratised tool follows the same arc: flourishing, then dependency, then atrophy. Each successive technology compresses the cycle faster.

Source: Author synthesis; Carr, The Shallows (2010); National Numeracy (2019); Dahmani & Bohbot (2020)

Because history also says it does not last.

Every democratisation of a cognitive tool follows a remarkably consistent four-phase pattern: democratisation → flourishing → convenience dependency → skill atrophy.

Consider writing itself. The spread of mass literacy in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries produced the flourishing described above: novels, newspapers, constitutions, scientific papers. But by the late twentieth century, most literate people used writing primarily for shopping lists, text messages, and bureaucratic forms. The capacity for sustained, complex written argument — which mass literacy had made theoretically universal — atrophied in practice. Most people can write an essay; most people don’t. The tool was democratised, the flourishing occurred, and then the population settled into a comfortable minimum of engagement with the skill.

The pattern repeats with every tool:

Calculators. Introduced widely in the 1970s and 1980s, electronic calculators initially enhanced mathematical capability — students could tackle more complex problems, engineers could work faster. Within a generation, most people could not perform mental arithmetic that their grandparents had done routinely. A 2019 study by the National Numeracy charity found that nearly half of working-age adults in the United Kingdom had the numeracy skills of a primary school child.

GPS navigation. When satellite navigation became standard in vehicles and smartphones in the 2000s, it initially empowered people to travel more confidently to unfamiliar places. Within a decade, research showed measurable atrophy in spatial cognition among heavy GPS users. A 2020 study in Nature Communications found that using GPS navigation consistently reduced hippocampal engagement and impaired the ability to form cognitive maps.

Spell-checking. Autocorrect and spell-check made professional-quality spelling accessible to everyone, regardless of natural spelling ability. Studies consistently show that reliance on spell-check correlates with declining spelling accuracy when the tool is unavailable.

The pattern is not that the tools are bad. Each tool genuinely democratised a capability and produced a genuine flourishing. The pattern is that humans are rational: when a tool can do something for you, most people let it, and the underlying skill gradually decays. Nicholas Carr’s The Shallows (2010) documented this tendency across multiple cognitive domains, arguing that the internet itself was rewiring our capacity for deep reading and sustained attention.

Applied to AI, the pattern suggests three phases:

Phase 1 (now): People use AI to do things they could not do before — build apps, produce films, design brands. This is pure gain. The teacher who builds a classroom app is not losing a skill she previously had; she is gaining a capability she never had. The small business owner producing video adverts is not forgetting how to use Final Cut Pro; he never knew.

Phase 2 (near future): People begin using AI to do things they could do but AI does faster and better. The professional designer uses AI for layouts she once composed herself. The developer uses AI for code he once wrote manually. The writer uses AI for drafts she once laboured over. Efficiency increases. The underlying skills, unused, begin to erode.

Phase 3 (further out): People cannot do things without AI because they never learned or have forgotten. The designer cannot compose a layout without AI assistance. The developer cannot debug without an AI agent. The writer cannot structure an argument without AI scaffolding. The tool has become not an amplifier but a prosthetic — and, like any prosthetic, removing it reveals the atrophied limb beneath.

How long does Phase 1 last? History suggests the flourishing typically spans one to two generations — roughly twenty to fifty years — before dependency becomes the dominant mode. The printing press triggered a flourishing that lasted perhaps two centuries (roughly 1500–1700) before mass literacy settled into its comfortable, utilitarian baseline. Calculators took perhaps one generation — twenty to thirty years — before mental arithmetic was broadly lost. GPS took less than a decade.

The acceleration is itself a pattern. Each successive tool collapses the flourishing phase faster than the last, because each tool is more comprehensive and more convenient than its predecessor. If calculators took thirty years and GPS took ten, it is not unreasonable to ask whether AI — which is the first tool that can do nearly everything the human can do, rather than just one narrow task — might compress the cycle to five or ten years.

The Optimistic Case

There is, however, a reason to believe that AI might break the pattern rather than merely accelerate it.

Every previous tool in the dependency cycle was specific: calculators did arithmetic, GPS did navigation, spell-check corrected spelling. Once the tool handled the task, there was no reason to engage with the underlying skill. But AI is general. It is a creative collaborator, not just a calculator. The teacher using AI to build a classroom app is not pressing a button and receiving a finished product; she is describing, iterating, refining, testing, and improving. The interaction requires judgement, taste, and vision — qualities that may deepen with use rather than atrophy.

If this is correct, AI might sustain the flourishing longer than any previous tool, because it keeps the human engaged rather than passive. The printing press made readers; AI might make directors — people who do not perform every task themselves but who orchestrate outcomes with skill and intention.

The Pessimistic Case

But the pessimistic case is equally plausible. The history of convenience is the history of humans choosing the path of least resistance. When AI can produce a perfectly adequate film from a one-sentence prompt, how many people will spend hours refining their creative vision? When AI can generate a flawless marketing strategy in seconds, how many business owners will develop their own strategic thinking? The gap between “adequate” and “exceptional” is where human skill lives — and most people, most of the time, will settle for adequate.

The Sumerian merchant did not need to write brilliantly; he needed to communicate a message about copper. The modern entrepreneur does not need to code brilliantly; she needs a functioning app. If AI provides the adequate result, the incentive to develop deeper capability evaporates. The flourishing becomes a flash — a brief, bright moment before the species settles into comfortable dependency.

Conclusion: Literacy and Literature

Return, one last time, to the merchant in Ur. He needed two scribes to send a single message. Today, his descendant dictates a voice note on a smartphone and it arrives instantly, transcribed, translated, and formatted. The scribes are gone. Nobody mourns them.

The digital scribes — developers, designers, agencies, production companies — are the scribes of our age. Their monopoly over the means of digital creation, which has lasted roughly sixty years, is ending. The barrier between the individual and the medium is collapsing. The flourishing has begun, and it is already producing marvels that the scribal economy could never have delivered: millions of perfectly tailored applications, a torrent of creative expression, small businesses competing with the capability of corporations.

But spare a thought for what comes after. When everyone could write, most people stopped thinking carefully about words. When everyone could calculate, most people stopped thinking carefully about numbers. When everyone could navigate, most people stopped thinking carefully about where they were. The tool democratised the capability, the flourishing occurred, and then — slowly, imperceptibly — the capability itself withered through disuse.

The distinction that matters is the one between literacy and literature. Mass literacy gave everyone the ability to write; it did not make everyone a writer. The printing press gave everyone access to books; it did not make everyone a reader of depth and discernment. The question for AI is whether it produces a civilisation of creators — people who use these extraordinary tools to express and build things of genuine meaning — or a civilisation of consumers — people who prompt, accept, and scroll.

The scribes are dying. Long live the scribes. The question is what we do with our freedom.