In 2023, a team of economists at the University of Amsterdam published a study with a title that would have been unpublishable in most Western universities a decade earlier: Borderless Welfare State: The Consequences of Immigration for Public Finances. Using anonymised microdata from Statistics Netherlands covering all 17 million residents, they calculated the lifetime fiscal contribution of every immigrant and their descendants — taxes paid minus benefits received, from arrival through death — differentiated by origin country, immigration motive, and generation.

The headline finding: immigration had cost the Netherlands approximately €17 billion per year on average between 1995 and 2019. That is €400 billion over a quarter of a century. Projected forward at current patterns, the next two decades would cost a further €600 billion. For a country of 18 million people, these are not rounding errors. They are the equivalent of the entire Dutch defence budget, every year, for twenty-five years — spent not on frigates and fighter jets, but on the gap between what immigrants contribute to the treasury and what they receive from it.

Across the North Sea, Denmark had been publishing similar data for years — and, unlike the Netherlands, had actually done something about it. The Danish Ministry of Immigration reported that non-Western immigration cost the state 31 billion Danish kroner (approximately €4.2 billion) in 2018 alone. Denmark’s population is barely a third of the Netherlands’. Per capita, the Danes were paying even more. But by the time these figures were published, Denmark had already embarked on the most aggressive course correction in European immigration policy. The Netherlands, confronted with the same arithmetic, dithered for another decade.

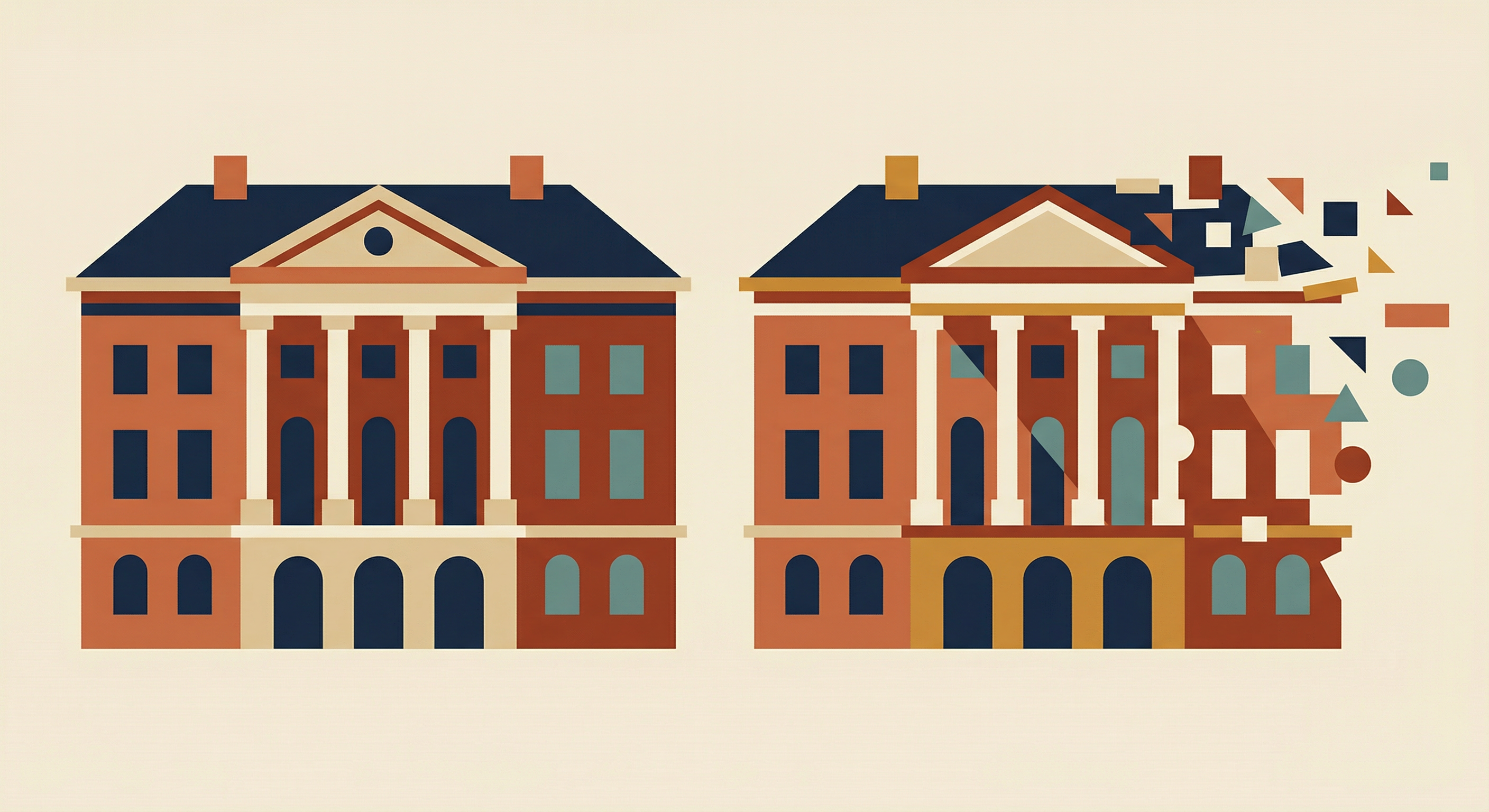

These two countries are the closest thing to a controlled experiment that European immigration policy has ever produced. Similar size. Similar wealth. Similar Protestant-heritage welfare states with universal benefits, high trust, and statistical agencies that — unlike their counterparts in France or Britain — were willing to disaggregate the data by origin. Both received the same answer. One acted. One did not. The divergence in their political trajectories since tells you everything about the cost of ignoring arithmetic.

Netherlands: Lifetime Fiscal Impact per Immigrant by Origin

Net lifetime fiscal contribution (taxes paid minus benefits received) — Van de Beek et al., 2023

Source: University of Amsterdam, "Borderless Welfare State" (2023), using Statistics Netherlands microdata

The Dutch Ledger

The Van de Beek study did what most governments refuse to do: it put a price tag on immigration, broken down by where people came from and why they arrived. The results varied by a factor of forty.

Immigrants from North America, Japan, the United Kingdom, and Scandinavia contributed between €194,000 and €208,000 per person over their lifetimes — net positive, handsomely so. Labour migrants aged twenty to fifty contributed over €100,000 each. Western immigrants as a group averaged a net gain of €25,000. These are the immigrants that every country wants and few immigration debates are actually about.

At the other end of the ledger, the figures were rather less cheerful. Family migrants cost between €200,000 and €275,000 per person. Asylum seekers averaged €475,000. Immigrants from Turkey cost €340,000. Those from Afghanistan, Syria, and Iraq: €418,000. From Morocco: €542,000. From the Horn of Africa and Sudan: €606,000 per person — a net lifetime fiscal cost equivalent to a comfortable house in Amsterdam, per individual, paid for by Dutch taxpayers.

The average non-Western immigrant represented a lifetime cost of €275,000. The study found that cultural distance to Protestant Europe was the single strongest predictor of fiscal outcomes, even after controlling for education levels. The further the origin country from northwestern European cultural norms, the larger the deficit. This is not a finding that any politician wants to discuss. It is also not a finding that any honest economist can ignore.

The Second Generation

Perhaps the most consequential finding concerned the children. The conventional argument for accepting short-term fiscal costs from immigration is that the second generation will integrate, earn more, and close the gap. The Dutch data says otherwise.

Second-generation immigrants in the Netherlands achieve educational outcomes broadly comparable to native Dutch children. They attend the same schools, pass the same examinations, obtain similar qualifications. But they earn systematically less for the same level of education. The gap is not in schooling. It is in what the researchers delicately called “benefits from schooling” — the translation of qualifications into income. Equal degrees, unequal incomes, and therefore unequal fiscal contributions. The deficit does not close in the second generation. It persists.

Netherlands: Projected Population by Origin to 2050

Dutch-origin share projected to fall from 73% to between 58% and 66% depending on migration levels

Source: Statistics Netherlands (CBS), Population Outlook 2050 (2024)

Crime

The Netherlands is one of the few European countries where the national statistics bureau publishes crime suspect rates by ethnic background. The data, as of 2017, shows persistent overrepresentation: residents of Antillean background were registered as crime suspects at 4.4% — six times the native Dutch rate of 0.7%. Moroccan background: 3.7%, down from 7.4% in 2005. Surinamese: 2.8%. Turkish: 2.0%. All groups have improved significantly over the past two decades, but the ratios remain striking.

The most arresting statistic concerns second-generation Moroccan men. More than half — and by some estimates as high as 65% — have been charged with a criminal offence by the age of twenty-three. This is the second generation, not the first. The first generation of Moroccan immigrants actually had below-average crime rates. Something went wrong in the transmission — and it went wrong in the country that was supposed to have integrated them.

The Demographic Trajectory

As of January 2025, 16.8% of the Netherlands’ 18 million inhabitants were born abroad. A further 11.7% were born in the Netherlands to one or both foreign-born parents. Total population with a migration background: approximately 28.5% — nearly three in ten. Amsterdam and The Hague already have majority non-Dutch-origin populations. Statistics Netherlands projects that the Dutch-origin share will fall from 73% in 2023 to between 58% and 66% by 2050, depending on migration levels. The transformation is irreversible on any policy-relevant timescale.

The Danish Ledger

Denmark collects and publishes immigration fiscal data with a thoroughness that borders on the obsessive — and then uses it to make policy. The Ministry of Immigration’s annual reports break costs down by Western versus non-Western origin, and further by the MENAPT category (Middle East, North Africa, Pakistan, and Turkey) that Denmark invented and that no other European government dares to use.

The 2018 figures: non-Western immigration cost the Danish state 31 billion DKK — down from 42 billion in 2015, a reduction the government attributed to tighter policies. MENAPT immigrants and their descendants, who constituted 55% of all non-Western immigrants, accounted for 77% of the cost: 24 billion DKK, or approximately 85,000 DKK (€11,400) per person per year. Immigrants from Western countries, meanwhile, were net fiscal contributors.

Denmark: Employment Rates by Origin Group (2015 vs 2022)

Employment gap has narrowed to a record low of 15.3 percentage points — but persists

Source: Statistics Denmark; The Local Denmark (2023, 2024)

The drivers are straightforward: lower employment rates combined with universal welfare. In 2022, ethnic Danish men had an employment rate of 81%, ethnic Danish women 79%. Non-Western immigrant men had reached 69% — up from 53% in 2015, a genuine improvement. Non-Western immigrant women: 58%, up from 45%. The gap has narrowed to a record low of 15.3 percentage points. But a 15-point employment gap applied to hundreds of thousands of people still generates billions in welfare expenditure and lost tax revenue.

Denmark’s long-term demographic projection is sobering. Immigrants and descendants already account for 16.3% of the population (Western and non-Western combined). Statistics Denmark projects that the non-Western share alone will reach 13.1% by 2060, up from roughly 9% today. The more striking number comes from longer-range modelling: by 2096, the majority of Denmark’s population could consist of immigrants or their descendants. Ethnic Danes would become a minority in their own country within the lifetimes of children born today.

The Danish Response: A Paradigm Shift

Denmark read the data and acted. The political story is as remarkable as the fiscal arithmetic.

In 2016, the Danish parliament passed the “jewellery law” — legislation permitting police to confiscate cash exceeding 10,000 DKK and valuables from asylum seekers upon arrival. Wedding rings were exempt. The bill passed 81 to 27, with support from the centre-left Social Democrats. International outrage was considerable. Danish public opinion was unmoved.

In 2018, the government published “One Denmark Without Parallel Societies: No Ghettos in 2030.” The plan identified twenty-eight neighbourhoods where more than 50% of residents were immigrants or descendants from non-Western countries and where additional criteria — low employment, low education, high crime, low income — were also met. These areas were officially designated as ghettos, using the government’s own word. The policy response included demolishing and redeveloping social housing to cap the non-Western share, doubling criminal penalties within designated zones, and mandating nursery attendance from age one — twenty-five hours per week — with instruction in “Danish values” and the Danish language.

In February 2025, an EU Court of Justice adviser ruled that using ethnic origin to classify neighbourhoods constituted direct discrimination. Denmark’s response, historically, has been to note such rulings and continue regardless.

In 2019 came the paradigmeskift — the paradigm shift. All refugee residence permits became temporary. The maximum initial term was two years. Permanent residency became possible only after eight years. The word “integration” was largely struck from legislation and replaced with “self-sufficiency and return.” Social benefits for refugees were cut to approximately half of what Danish citizens receive. Authorities gained the power to revoke protection status if conditions in origin countries showed even slight improvement.

The most politically significant aspect of the paradigm shift was who delivered it. The 2019 law was supported by the Social Democrats, who then won the election and intensified the restrictions under Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen. A centre-left party — committed to the welfare state, to universal healthcare, to generous pensions — concluded that the welfare state could not survive unrestricted immigration, and that restricting immigration was therefore a progressive, not a conservative, position. Frederiksen framed the argument in precisely those terms: protecting the welfare model meant controlling who could access it.

The electoral consequence was striking. The Danish People’s Party, which had built its support almost entirely on anti-immigration sentiment, collapsed. Its signature issue had been adopted by the mainstream. There was nothing left to vote for. Denmark demonstrated that when a centre-left party addresses immigration honestly, the populist right loses its reason to exist.

And there are signs it is working beyond the ballot box. Research on second-generation descendants of immigrants from Muslim countries in Denmark found that 80–90% perform comparably to ethnic Danes on income, tax payments, benefits receipt, and school grades. Among those aged thirty-five to forty, there is a 91% overlap in income distribution between immigrant descendants and native Danes. Denmark’s strict requirements — language proficiency, employment expectations, cultural orientation — appear to be producing integration outcomes that the Netherlands’ more permissive approach has not.

The Dutch Response: Too Late, Too Loud

The Netherlands took the opposite path. Not the opposite data — the opposite response.

For decades, mainstream Dutch parties avoided immigration as a political topic. The consensus was that the Netherlands was a tolerant, multicultural society, and that questioning this was at best impolite and at worst racist. Pim Fortuyn, who challenged this consensus, was assassinated in 2002. Theo van Gogh, who made a film about Islam and women’s rights, was murdered in 2004. The message to anyone contemplating public discussion of immigration was not subtle.

The dam broke at Ter Apel. In the summer of 2022, the Netherlands’ main asylum reception centre — designed for 2,000 residents — became so overcrowded that over 700 asylum seekers were sleeping outside on muddy ground, without access to showers, food, or medical care. A three-month-old baby died. Médecins Sans Frontières — an organisation that normally deploys to war zones and famine-struck countries — sent a team to the Netherlands for the first time in its history. The images were broadcast across Europe.

In July 2023, Mark Rutte’s coalition government collapsed over a failure to agree on asylum policy. In the November election that followed, Geert Wilders’ PVV — the Party for Freedom, which had campaigned on “zero asylum seekers” and “borders closed” — won thirty-five seats, the most of any party. Eighty per cent of PVV voters cited immigration as their primary motivation. The new four-party coalition announced “the strictest-ever asylum regime.”

But here is where the Dutch story becomes a cautionary tale about supranational governance. Most of the PVV’s immigration proposals are legally impossible under existing EU law, the European Convention on Human Rights, and freedom of movement regulations. The Netherlands cannot unilaterally restrict asylum, impose quotas, or require work permits for EU citizens. The voters delivered a democratic mandate. The EU legal framework blocks its implementation. The gap between what the Dutch electorate voted for and what the Dutch government can deliver is the gap between national democracy and supranational constraint — and it is precisely the gap that breeds the disillusionment with democratic institutions that populist parties feed on.

The Lesson

Denmark and the Netherlands are not a story about immigration. They are a story about timing, honesty, and the courage to act on evidence.

Both countries had the data. Both had statistical agencies willing to publish it. Both had electorates that wanted action. The difference is that Denmark acted when action was still within the gift of a national government, and the Netherlands waited until the problem was so large that its own legal commitments made a solution nearly impossible.

Denmark’s Social Democrats proved that immigration restriction is not inherently a right-wing position. It is a welfare-state position. A universal welfare system funded by taxation cannot survive if a significant proportion of its beneficiaries are net fiscal liabilities. The arithmetic is indifferent to ideology. Frederiksen understood this. The Dutch political class, until Ter Apel made denial untenable, did not.

The deeper lesson is about what happens when governments possess data and refuse to act on it. The Van de Beek study was not a surprise. The underlying patterns had been visible in Dutch statistics for decades. The €17 billion annual cost did not materialise overnight. It accumulated, year after year, while successive governments looked away — because acknowledging the fiscal reality of immigration would have required policy changes that the political class found culturally uncomfortable. The cost of that comfort, over twenty-five years, was €400 billion.

Denmark spent its political capital early and bought itself a functioning immigration policy, improving integration outcomes, and a political landscape in which the far right has been neutralised. The Netherlands spent nothing, and bought itself Ter Apel, the PVV, a collapsed government, and a democratic mandate that EU law will not allow it to fulfil.

The data was the same. The price of ignoring it was not.