Most political positions today are argued from feeling. The left feels that equality is the supreme good and that the state is the instrument to achieve it. The right feels that tradition should be preserved and that change is inherently suspect. Each side wraps its instincts in selective evidence, ignores the rest, and calls the result policy. The debates between them generate enormous heat and remarkably little light.

This publication takes a different approach. We started with a question: what did civilisations that lasted a thousand years do differently from those that burned out in a century? Not what ought to work, in a just and rational world. Not what feels right to people with the correct education. What actually worked — across five thousand years of recorded history, on every inhabited continent, in societies that had nothing in common except that they endured.

The answer is remarkably consistent. From the Nile Delta to the Swiss Alps, from Republican Rome to Edo-period Japan, the civilisations that lasted the longest and produced the most — culturally, economically, intellectually — shared a set of structural features so uniform that they begin to look less like policy preferences and more like engineering requirements. The positions this publication holds are derived from that evidence. They are not conservative or progressive. They are not left or right. They are what the historical record says, read without flinching.

If this makes us populists — a label the administrative class deploys the way medieval priests used “heretic” — then Pericles was the original Reform Party member, and Augustus ran on a platform of controlled borders and fiscal discipline. We are content with the company.

The Measure of Success

What does it mean for a civilisation to succeed? Not mere survival — plenty of miserable polities have lingered for centuries. Success, as this publication defines it, requires the combination of durability, prosperity, cultural achievement, citizen wellbeing, and resilience under crisis. A civilisation that lasts a millennium but produces nothing of value has merely persisted. A civilisation that blazes brilliantly for a generation and collapses has merely entertained.

By this measure, a small number of civilisations stand apart. Ancient Egypt maintained a recognisable civilisation for three thousand years — longer than every modern European state combined. The Roman Republic and Empire together lasted over a millennium. China has sustained a continuous civilisational identity for four thousand years, absorbing Mongol and Manchu conquerors rather than being absorbed by them. Japan has maintained cultural continuity for over fifteen hundred years. The Swiss Confederation has endured since 1291. The Republic of Venice lasted eleven hundred years, governing with a sophistication that made its diplomatic corps the envy of Europe. The Byzantine Empire persisted for eleven centuries after the western half of Rome had fallen.

Civilisation Longevity: The Durable vs. the Disposable

Duration of major civilisations and states in years — culturally cohesive, locally governed polities dominate the top of the chart

Source: Various historical sources; dates are approximate and use conventional periodisation

For contrast, consider the experiments that failed. The Soviet Union lasted sixty-nine years. Yugoslavia survived for seventy-three. The Habsburg Empire — that vast administrative apparatus stretching from Belgium to Transylvania — spent most of its existence fracturing and was dissolved the instant real pressure was applied in 1918. Czechoslovakia managed seventy-five years. The European Union, as a political project with aspirations to statehood, has yet to celebrate its fortieth birthday and is already fraying at the seams.

These successful civilisations differed in virtually every respect — religion, climate, language, technology, geography. Egypt worshipped animal-headed gods; Rome sacrificed bulls; Japan venerated its ancestors; Switzerland is Protestant and Catholic in roughly equal measure. They had nothing in common except that they lasted. And yet, when you examine their structural features, the similarities are striking. The principles this publication advocates are not drawn from a single tradition or a single continent. They are the recurring patterns of civilisational success, observed independently across millennia.

Self-Governing Adults

Every durable civilisation expected its citizens to be capable adults. This is so consistent across time and geography that it begins to look less like a policy choice and more like a law of social physics.

In the Roman Republic, citizenship was inseparable from obligation. Citizens were soldiers, landowners, and participants in governance. The Roman citizen-farmer served in the legions during campaign season and returned to his fields afterwards. He was not a ward of the state. He was the state — a self-reliant individual whose personal competence was the foundation of collective strength. Athens went further: every citizen participated directly in governance, served on juries, and contributed to the city’s defence. This was not a right to be exercised if one felt inclined. It was a duty, and shirking it was contemptible. The Greek word for a citizen who took no part in public affairs was idiotes — from which, rather pointedly, we derive the English word.

The Swiss institutionalised individual responsibility with characteristic precision. The Landsgemeinde — the open-air assembly where citizens voted by show of hands — was direct democracy in its most unmediated form. Switzerland still maintains universal male conscription. Every citizen-soldier keeps his service weapon at home. The relationship between individual capability and collective security is not metaphorical. It is literal, physical, and stored in the hall cupboard.

Tokugawa Japan, during its two centuries of self-imposed isolation, built one of the most orderly and culturally productive societies in history on a foundation of extraordinary personal discipline. The ethic of self-discipline, duty, and personal responsibility was not reserved for the samurai class. It permeated the entire society, from merchant to farmer, producing a population so capable that when Japan was forcibly opened in the 1850s, it industrialised faster than any nation in history.

The counter-pattern is equally consistent. Late Rome’s annona — the grain dole — created an urban population of hundreds of thousands who depended entirely on the state for sustenance. By the fourth century, the Roman mob was a political weapon, mobilised by whoever controlled the grain supply. The citizens who had once conquered the Mediterranean now rioted when their bread was late. The Soviet Union’s comprehensive welfare state produced a population so conditioned to central provision that when the state collapsed in 1991, millions could not cope. Life expectancy for Russian men fell by six years in half a decade — the withdrawal symptoms of a society addicted to state dependency.

The principle is not complicated. Civilisations that expected adults to manage their own lives produced resilient, capable populations that could weather crises. Civilisations that absorbed responsibility from their citizens produced populations that could not survive without the apparatus that had infantilised them. The more a state does for its people, the less its people can do for themselves — and when the state falters, as all states eventually do, those people are helpless.

Govern Where You Can See

The Athenian citizen could see the Acropolis from his front door. This was not incidental to Athenian democracy. It was foundational. The polis was governance at human scale — small enough that every citizen knew the issues, knew the officials, and could hold them accountable in person. Aristotle argued that a city-state should be no larger than could be reached by a herald’s voice. He was making a point about accountability, not acoustics.

The Swiss Confederation has maintained this principle for over seven hundred years. Twenty-six cantons govern a population smaller than London’s. Decisions are made at the lowest possible level — commune, then canton, then federal government. The federal government handles defence, foreign affairs, and a narrow band of national concerns. Everything else is local. The result is one of the most prosperous, stable, and well-governed countries on earth — a nation that has not fought a war since 1847 and yet maintains a citizen army that could mobilise 100,000 soldiers within forty-eight hours.

Medieval Italy’s city-states were small, self-governing, and staggeringly productive. Venice, a city of fewer than 200,000, dominated Mediterranean trade for centuries and produced an artistic and intellectual output that puts modern states fifty times its size to shame. Florence, under the Republic, gave the world the Renaissance — not as the product of centralised cultural planning, but as the natural output of a self-governing community where talent, ambition, and civic pride intersected. These were not planned outcomes. They were emergent properties of self-governance at human scale.

The counter-pattern is grimly predictable. The late Roman Empire centralised everything in Constantinople and Rome, creating a bureaucratic apparatus so vast and so distant from the provinces it governed that it could not respond to local crises. When the Visigoths crossed the Danube in 376, the imperial response was catastrophic — not because Rome lacked resources, but because decisions required approval from officials a thousand miles away who had never visited the frontier. The Qing Dynasty governed 400 million people from Beijing through a civil service that was superbly educated and almost entirely disconnected from provincial reality. The Soviet Union’s central planners produced surpluses of goods nobody wanted and shortages of goods everybody needed, because the information required to allocate resources efficiently existed at the local level and could not be transmitted upward through the bureaucratic chain without being distorted beyond recognition.

The distance between governance and the governed is inversely correlated with civilisational health. This is not a left-wing or right-wing observation. It is an engineering one, confirmed across every century and continent for which we have records.

The Coherent People

Ancient Egypt lasted three thousand years. This is difficult to grasp in a civilisation where political arrangements rarely survive a century. Egyptian civilisation endured for thirty times longer than the Soviet Union, forty times longer than the European Union has existed, and roughly ten times longer than every modern Western democracy. The foundation was not military power — Egypt was conquered repeatedly. It was cultural coherence: a unified language, a shared religious framework, a common identity so powerful that foreign conquerors — Hyksos, Persians, Ptolemaic Greeks — were absorbed into the Egyptian cultural world rather than replacing it. The conquerors changed. Egypt did not.

Japan preserved its cultural identity through deliberate policy for two millennia. The sakoku period — 220 years of near-total isolation — was the most extreme expression of this principle, but the impulse preceded and outlasted it. When Japan opened to the world in the 1850s, it modernised faster than any nation in history. This was not despite its cultural cohesion but because of it. A society that knows who it is can adopt foreign technologies and methods without losing itself. A society that does not know who it is cannot adopt anything without being consumed by it.

China’s civilisational identity is so powerful that it absorbed every invader. The Mongol Yuan Dynasty and the Manchu Qing Dynasty both adopted Chinese language, Chinese administrative systems, and Chinese culture. The invaders became Chinese. The civilisation persisted. Four thousand years of continuity is not an accident. It is the product of a people who knew, with absolute clarity, who they were and what they valued.

Rome before the Edict of Caracalla (AD 212) treated citizenship as something earned and jealously guarded. The Italian allies fought a war — the Social War of 91–88 BC — simply to obtain it. When Caracalla granted citizenship to virtually everyone in the empire, he did not strengthen Rome. He rendered Roman identity meaningless. Within two generations, the Roman army was staffed by Germanic soldiers who fought for pay rather than for any notion of what Rome was. The Habsburg Empire — a patchwork of Germans, Hungarians, Czechs, Croats, Poles, Italians, Romanians, and Slovaks held together by a dynasty and little else — dissolved the instant the dynasty fell. Yugoslavia, an artificial state stitching together peoples with centuries of mutual grievance, lasted one human lifetime and ended in genocide.

The principle applies universally — to Japan, Nigeria, Hungary, Thailand, and Britain alike. Nations with a clear, shared identity endure. Nations that dissolve their distinctiveness do not. This is not a Western conceit. It is a civilisational observation, confirmed on every continent.

Sound Money, Solvent States

Under Augustus, the Roman denarius contained 95 per cent silver. By AD 268, under Gallienus, that figure had fallen to 0.5 per cent. The debasement tracks almost precisely with the empire’s political and military decline — not because debased coins alone destroyed Rome, but because the debasement was both symptom and accelerant of the same fiscal incontinence that rotted the state from within. When a government spends more than it earns, it has three options: raise taxes, borrow, or debase the currency. Rome tried all three, in sequence and then simultaneously, and collapsed.

The Debasement of the Roman Denarius

Silver content of Rome's principal coin declined from 97% to 0.5% as the empire spent beyond its means

Source: Numismatic data from Harl (1996), Walker (1976); percentages are silver purity by weight

The Song Dynasty invented paper money in the tenth century — a genuine innovation. Within two hundred years, the government had printed so much of it that hyperinflation destroyed its value entirely. The Ming Dynasty, having observed the consequences, abandoned paper currency and returned to silver and copper coin. Habsburg Spain received more New World silver than any polity in history — the treasure fleets of the sixteenth century poured wealth into Castile on a scale that had no precedent. Philip II still managed to declare state bankruptcy four times in a single century, because expenditure on wars, palaces, and bureaucracy outpaced even that extraordinary windfall (Drelichman and Voth, 2014).

The pattern repeats without exception across every era. Weimar Germany. Nationalist China. Argentina — which has defaulted nine times since independence. Zimbabwe. Venezuela. Every state that debased its currency or spent beyond its means followed the same trajectory: short-term relief, medium-term inflation, long-term ruin.

Every major Western government today is running structural deficits. Total government debt in the G7 exceeds 100 per cent of GDP. The United States alone owes more than $36 trillion — a figure so large that the annual interest payments now exceed the entire defence budget. The United Kingdom’s national debt has passed 100 per cent of GDP for the first time since the 1960s. The trajectory is identical to Rome’s, Spain’s, and every other great power that borrowed its way to prominence and then borrowed its way to ruin. This is not austerity ideology. It is arithmetic, confirmed across every century of recorded history.

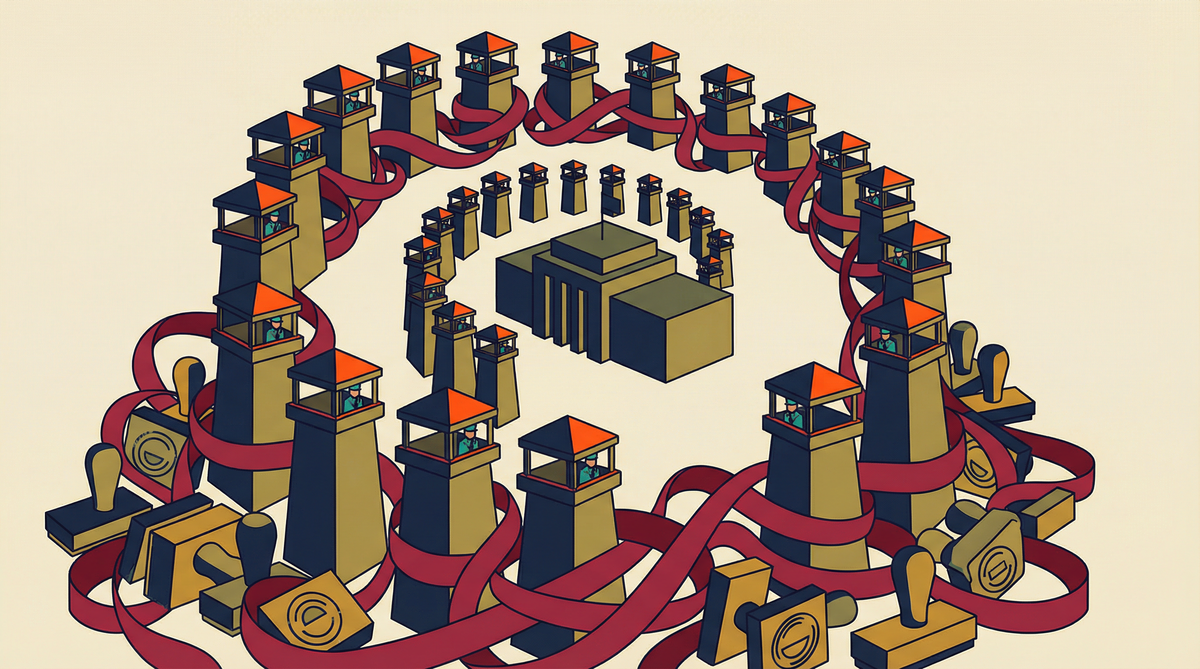

Who Serves Whom?

Every class created to serve the state eventually captures it. The Ottoman Janissaries, created as loyal slave-soldiers with no family ties, became a hereditary caste that murdered sultans who threatened their privileges. China’s eunuch administrators, recruited precisely because they could have no dynastic ambitions, became the most powerful faction at the imperial court. The Roman Praetorian Guard, created to protect the emperor, auctioned the throne to the highest bidder in AD 193. The pattern is universal and exceptionless: the servants become the masters.

The Growth of the State: Government Spending as % of GDP, 1900–2025

Total government expenditure has grown from roughly 10% to over 40% of GDP across every major Western economy

Source: Tanzi & Schuknecht (2000), IMF Fiscal Monitor, OECD Government at a Glance

The modern Western bureaucracy follows the same trajectory on a grander scale. In 1900, government spending across the West averaged roughly ten per cent of GDP. By 2025, it exceeds forty per cent in every major economy — forty-four per cent in Britain, forty-seven per cent in Germany, fifty-seven per cent in France. The regulatory apparatus has grown in lockstep: the United States Code of Federal Regulations now exceeds 180,000 pages. No elected official, let alone any citizen, has read it. No one can. The UK tax code runs longer than the complete works of Shakespeare — several times over.

The Bureaucratic Ratchet: US Code of Federal Regulations

Total pages in the Code of Federal Regulations — the cumulative weight of the regulatory state

Source: Federal Register / National Archives; George Washington University Regulatory Studies Center

The bureaucracy that administers this apparatus is unelected, permanent, and structurally resistant to democratic mandates. Ministers serve for two years on average. The senior civil servants who brief them have been in post for decades. When voters elect governments that promise change, the bureaucracy resists, delays, reinterprets, and waits them out. The voters notice. They elect more radical outsiders. The establishment calls these outsiders “populists” — which is merely the word the administrative class uses for democratic accountability, the way the Ottoman court called anyone who challenged the Janissaries a traitor.

The rise of so-called populist movements across the West is not a crisis of democracy. It is democracy reasserting itself against an administrative class that had insulated policy from the people who pay for it. The Roman tribunes were created to give the plebeians a voice against the patricians. The Reformation was a populist revolt against an unaccountable clerical bureaucracy. The English Parliament evolved specifically to constrain royal overreach. In every case, the pattern is the same: when the governing class stops serving the governed, the governed force a correction. This is not a bug in democracy. It is the feature.

The Future We Are Building

These principles are not nostalgia. They are not a wistful longing for Athens or the Roman Republic. They are a forward-looking blueprint for human flourishing, grounded in the most extensive evidence base available to any policymaker: the entire recorded history of human civilisation.

The goal of this publication is not to win culture wars. It is to identify the conditions under which human societies thrive — and to advocate for those conditions with every tool available, including the technologies that are reshaping the world. Artificial intelligence can restore subsidiarity at a scale the Athenians could not have imagined. The agora worked because the polis was small enough for direct civic participation; AI can handle the coordination complexity that previously demanded centralised bureaucracies, enabling community-level governance for populations of millions. Digital tools can deliver the transparency and accountability that self-governing citizens require. Blockchain can enforce the fiscal discipline that politicians will not. Technology is not the enemy of these ancient principles. It is their greatest enabler.

The vision is not complicated. A world of distinct, self-governing nations — culturally cohesive within, genuinely diverse between. Strong individuals and strong families who take responsibility for their own lives, rather than outsourcing their agency to a state that will inevitably serve itself. Sound public finances maintained by governments that live within their means. Accountable governance at every level, from the parish council to the parliament. Bilateral cooperation between sovereign nations, not supranational bureaucracies accountable to no electorate.

The West is currently running the opposite experiment — bloated states, dissolving identities, debased currencies, distant governance, and populations increasingly dependent on institutions that serve themselves. The historical record tells us how this experiment ends. It has been run before, many times, on every continent. It ends the same way every time.

These positions are not on the left or the right. They are on the side of the evidence — five thousand years of it, across every continent and culture. The civilisations that embraced these principles flourished. Those that abandoned them declined. The only question that remains is whether we have the will to read the record honestly and the courage to act on what it says.

The future is not written. But the blueprints are, and they have been for a very long time.